No mother should die bringing life into the world.

The Background

The United States alarmingly has the highest maternal death rate among developed nations in the world with nearly 700 women dying every year due to pregnancy related complications (Anderson & Roberts, 2019; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 2019). Three out of five of these deaths are preventable (CDC, 2019). The CDC (2019) defines pregnancy-related death as the death of a women while pregnant or for up to one year following the end of pregnancy from any cause related to or aggravated by the pregnancy or its management, excluding accidental or incidental causes. The outcome, duration, or site of the pregnancy is not significant.

With the advancement in medicine, one would think that maternal care was improving, however that is not the case. In 1990, 17 maternal deaths per every 100,000 pregnant women in the U.S. was recorded. By 2015, this number had risen to more than 26 deaths per 100,000 pregnant women. As this number continues to rise, American women are 50% more likely to die related to childbirth than their own mothers (Shah, 2018).

Pregnancy-related death can occur during pregnancy, delivery, or postpartum

- 31% occur during pregnancy

- 33% occur during delivery or up to one week after

- 36% occur between 1 week to 1 year postpartum (CDC, 2019)

So, what do these statistics mean? Perceptions of the reality of maternal death is likely misunderstood. It is not just occurring during or immediately following delivery, when many believe a woman is at highest risk. Over one-third of these deaths are happening after a woman is sent home with her baby. They are happening in our communities.

Who is it happening to?

The United States has failed to ensure a safety net that includes all mothers.

Barbara A. Anderson & Lisa R. Roberts

The maternal health crisis in the U.S. is largely influenced by economic, geographical, cultural, and racial factors, also referred to as social determinants of health (Anderson & Roberts, 2019). The stress experienced among women living in poverty impacts pregnancy, as well as long-term health (Lu, 2018). They may experience inadequate housing and transportation, lack of access to nutritious foods leading to obesity and gestational diabetes, lack of education, shortened maternity leave from work, inability to obtain childcare, lack of insurance, or decreased access to healthcare. Geography significantly affects maternal health. Often women living in rural communities have limited or no prenatal care, greatly increasing the risk for severe maternal morbidities. As many as 40% of counties within the U.S. lack even one qualified maternity healthcare provider. Decreased access to a tertiary maternity hospital among these communities further increases their risk of pregnancy-related death. The U.S. is a multicultural national that presents a variety of scenarios that could impact the care a woman receives, including language, immigration status, cultural norms, sexual orientation, gender identity, and age (Anderson & Roberts, 2019). The racial disparities in this country are perhaps the most alarming. Regardless of education, income, or other socioeconomic factors, African American women are three to four times more likely to die of pregnancy related causes than non-Hispanic white women (Anderson & Roberts, 2019). In fact, the pregnancy related mortality rate for African American women with at least a college degree was 5 times as high as white women with a similar education (CDC, 2019). The disparity is also apparent among other women of color. Below you will see the U.S. maternity mortality rate reported by the CDC in 2018.

- 47.2 deaths per 100,000 live births for black non-Hispanic women.

- 38.8 deaths per 100,000 live births for American Indian/Alaskan Native non-Hispanic women.

- 18.1 deaths per 100,000 live births for white non-Hispanic women.

- 12.2 deaths per 100,000 live births for Hispanic women.

- 11.6 deaths per 100,000 live births for Asian/Pacific Islander non-Hispanic women (Anderson & Roberts, 2019)

What are the causes?

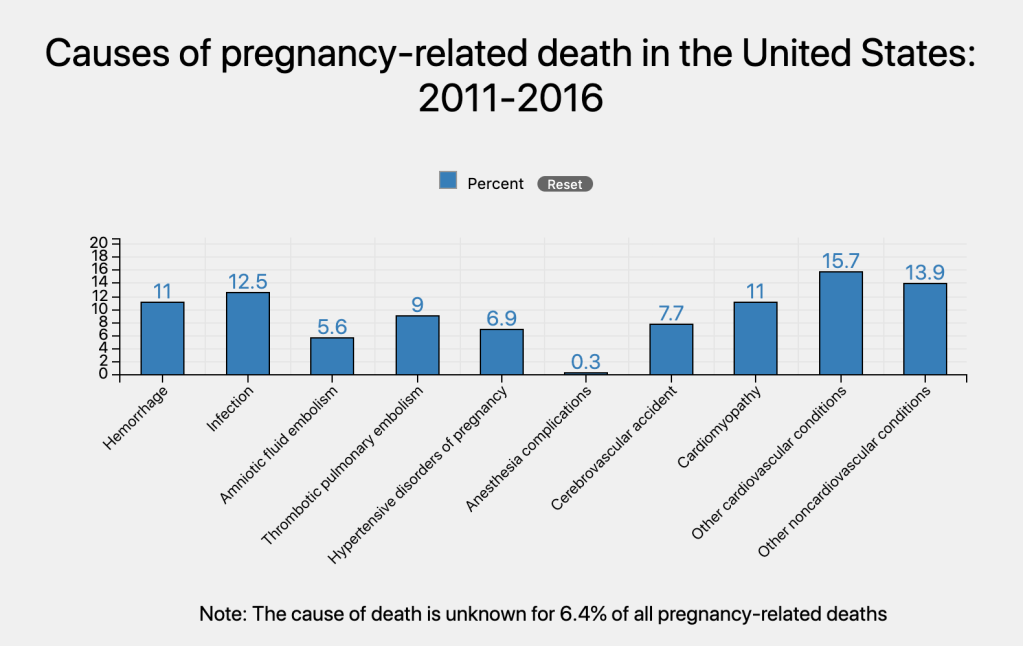

The number of pregnant women experiencing chronic health conditions, such as hypertension, diabetes, and chronic heart disease, is increasing in the U.S. These conditions put a pregnant woman at higher risk for complications. Although hemorrhage during and after delivery, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, and anesthesia related complications causing maternal death has decreased, the contribution of cardiovascular, cerebrovascular accidents, and other medical conditions have increased. Collectively, cardiovascular conditions account for greater than a third of pregnancy-related deaths (CDC, 2019).

What are we doing about it?

H.R. 1318: Preventing Maternal Deaths Act of 2018

To support States in their work to save and sustain the health of mothers during pregnancy, childbirth, and in the postpartum period, to eliminate disparities in maternal health outcomes for pregnancy-related and pregnancy-associated deaths, to identify solutions to improve health care quality and health outcomes for mothers, and for other purposes.

Despite these shocking trends, the U.S. has only recently joined the rest of the developed world putting in place infrastructure to systematically assess maternal deaths. On December 21, 2018 the president signed the bipartisan bill. The bill directs the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) to establish a program that allows grants to be directed toward states to review maternal deaths, establish a committee to review the gathered information, ensure the state department of health develops a plan for health care provider education to improve quality of maternal care, disseminate findings, and implement recommendations, and provide the public with the information included in state reports. States will develop procedures for mandatory reporting of maternal deaths by health care facilities and providers and voluntary reporting by family members. States will then investigate each case and prepare a case summary for review by the committee (GovTrack, 2018).

The story behind the bill.

I highly recommend you watch this video below. The man speaking is Charles Johnson IV who lost his wife Kira Johnson hours after she delivered their son via a scheduled Cesarean section. Refusing to allow this to happen to another family, he went to Capitol Hill to share his wife’s story with members of Congress, working alongside Representative Jaime Herrera Beutler, who experienced her own personal difficulties with pregnancy.

References

4KIRA4MOMS. (2018, June 4). Charles Johnson shares the tragic story of his wife Kira’s death hours after giving birth. [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=1&v=05uBCBfrY4g&feature=emb_logo

Anderson, B. A., & Roberts, L. R. (2019). The maternal health crisis in America: Nursing implications for advocacy and practice. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019). Maternal Mortality. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternal-mortality/index.html

GovTrack. (2018). H.R. 1318 (115th): Preventing Maternal Deaths Act of 2018. Retrieved from https://www.govtrack.us/congress/bills/115/hr1318

Lu, M. (2018). Reducing maternal mortality in the United States. JAMA, 320(12), 1237-1238. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.11652

Shah, N. (2018). A soaring maternal mortality rate: What does it mean for you? Harvard Health Publishing. Retrieved from https://www.health.harvard.edu/blog/a-soaring-maternal-mortality-rate-what-does-it-mean-for-you-2018101614914

Kara,

Thank you for blogging on this important topic.

Other recent efforts to tackle this terrible trend include:

The Alliance for Innovation on Maternal Health, (AIM) which works in partnership with the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG). Jointly they have created a set of “safety bundles” for best practices. The bundles include action plans for OB bleeding, severe high BP, and blood clots. They also address cutting racial disparities in care before and after birth.

United States Representative Ayanna Pressley, a democrat from Massachusetts has introduced an act called the Healthy MOMMIES Act to holistically approach maternity care with a community-based perspective that accounts for environmental causes and disparities.

The National Birth Equity Collaborative provides anti-racism and bias training focused on mothers and babies. The trainings are designed for use in hospitals, health departments, state governments and large nonprofits. The collaborative does research to inform their trainings.

Reference

Young, S. (2020, January 17). Confronting racial bias in maternal deaths. Retrieved from https://www.webmd.com/baby/news/20200117/confronting-racial-bias-in-maternal-deaths

From,

Karen Martinot

LikeLike

This is such an emotional and impactful topic, and I’m really glad you are addressing it in your blog this semester. The most staggering facts to me are the disparities between black women and white women with regards to maternal mortality. Many national organizations, such as the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, and the Maternal Child Health Bureau, have recognized these disparities and are working on implementing policies to correct them (Howell, 2018). It is also important to note that in addition to maternal mortality, maternal morbidity has increased (Howell, 2018). For each mother who dies during or after childbirth, there are 100 women who undergo life-saving procedures or receive life-threatening diagnoses during the same period (Howell, 2018). Many people will see the statistics you’ve mentioned in your post and attribute the difference to sociodemographic factors, such as the higher rate of poverty among minorities, leading to poorer health outcomes. What they may not realize is that the rate of maternal mortality is higher in black women regardless of their education, their income, or where they live (Howell, 2018). A black woman who has a higher education and a higher income is still more likely to die than a white woman who has a lower education and a lower income. We need to be asking ourselves as providers why this is happening and how we can help correct it.

As future nurse practitioners, we will be in a role that allows us to promote the changes necessary to correct these racial disparities. It is the responsibility of nurse practitioners and other healthcare providers to look for opportunities to influence both state and federal policies that will have a positive impact on their patient populations. Equity is one of the six aims of the Institute of Medicine, and is defined as providing “care that does not vary in quality because of personal characteristics such as gender, ethnicity, geographic location, and socioeconomic status” (Tomajan & Hatmaker, 2019, p. 49). In addition, the Code of Ethics for Nurses requires nurses to work with other healthcare providers to protect the public by promoting human rights and reducing health disparities (American Nurses Association, 2015).

I am looking forward to reading more about this topic as you continue working on your blog!

References:

American Nurses Association. (2015). Code of ethics for nurses with interpretive statements. Silver Spring, MD: Author.

Howell, E.A. (2018). Reducing disparities in severe maternal morbidity and mortality. Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology, 61(2), 387-399.

Tomajan, K., & Hatmaker, D.D. (2019). Advocating for nurses and for health In R.M. Patton, M.L. Zalon, & R. Ludwick (Eds.), p. 49. New York, NY: Springer.

LikeLike

Some epidemiologists point to higher maternal mortality rates related to advanced maternal age and/or higher-risk multiples pregnancies in the United States made possible by advanced conception care and technologies including IVF. To what degree does that type of medical advancement factor into the high maternal mortality rates in the United States?

LikeLike